Painting Is Like Writing

“Painting is like writing” - and vice versa - is a common phrase among artists.

A thought that pops up from time to time.

In this research the commonalities are addressed by programming a course of image generators investigating this topic.

The research does not prove this idiom, yet it is giving some reasoning of why this is a somewhat valid thought, from the historical timelines to nowadays art practices. Thus, overall it demonstrates that “Painting is like writing”, and writing is like painting - or even “painting is like writing is like programming” - as both engage the observer’s imagination, offering a dialogue between the artist’s intent and the audience’s interpretation. Ultimately, both are forms of storytelling and emotional expression, where acts blend to shape the mental and emotional landscapes they evoke. Though, the chosen method of the research is programming. A fact, that applies another layer to consider.

Who said “painting is like writing” - some examples and variations of the saying.

- Picasso “painting is like writing (a diary)”,

- Amy Sillman “For me painting is like writing. I like doing it myself.”

- Voltaire “Writing is the painting of the voice”

- Horace, the ancient Roman poet, coined the phrase “ut pictura poesis” (as is painting, so is poetry) in his “Ars Poetica

- Leonardo da Vinci famously stated, “Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen”

- Wassily Kandinsky wrote extensively on the relationship between painting and other art forms. In his book “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” he compared the visual elements of painting to musical notes and literary techniques

- and many others

1

Most artists focus on the poetic aspect of this common saying, others lay focus onto the daily practical. But all of them, writers, artists, philosophers, see the transition and the transfer between the arts. And sometimes not just between painting and writing, but between all the arts, acting, writing, painting, sculpture, music, dance and architecture.

This is where we must now consider programming not only as a functional tool and solution, but also as a new art form.

Why “painting is like writing” vice versa in one way or another:

… like programming -> programming as a transitional technique between writing and painting. Write a program in a mathematical language to generate, draw paintings.

before developing the first motif

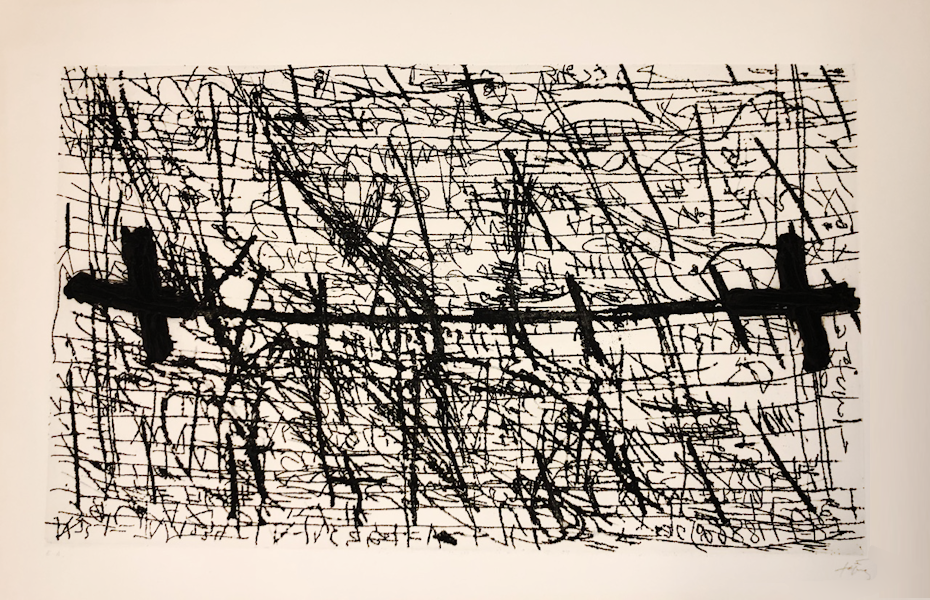

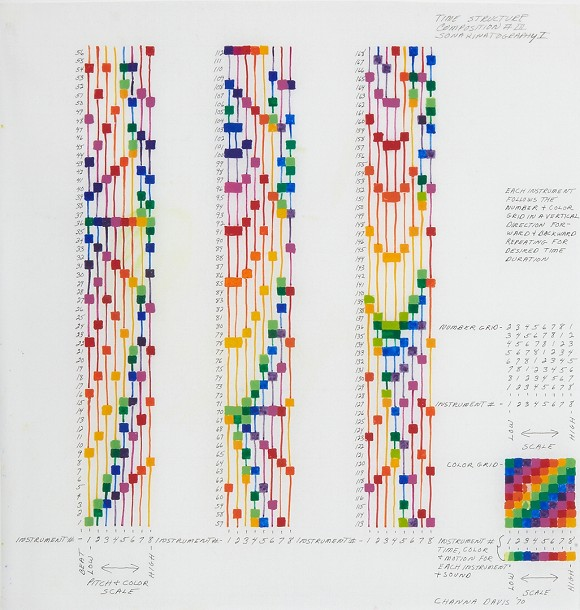

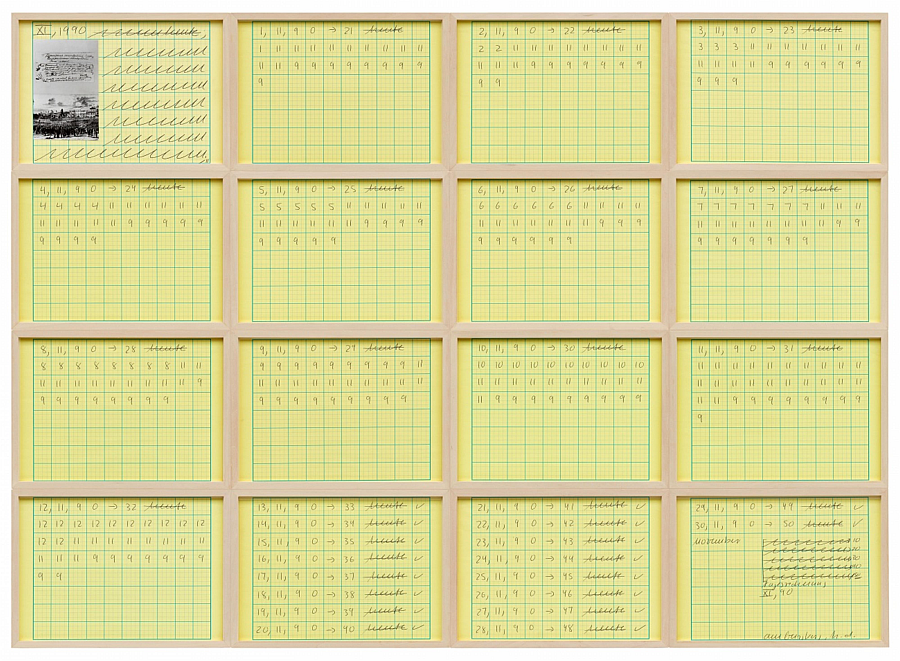

Artist, who utilized writing in their artworks before in one way or the other: Hilma Af Klint, Surrealists (automatic writing), Jenny Holzer, A. Tapies, Cy Twombly, Horwitz, Hanne Darboven and many others

| A.Tapies | Cy Twombly | Horwitz | Hanne Darboven |

|

|

|

|

Historically, many cultures have intertwined the practices of painting and writing. Ancient civilizations like Egypt, Hieroglyphs, Mesopotamia, Cuneiforms, and Ancient China developed pictographic forms of writing that were inherently visual, and in China calligraphy, respectively as an intermedia discipline. Mayan pre 500BC-1697ad 2, Aztec, though developed later are other independent branches, which exemplifies this path from painting, formalization to a writing system. Aztec seems to be the less advanced of all examples.

These early forms of communication were as much about aesthetics as they were about conveying meaning. In these societies, writing was not only a tool for documentation but also an art form, with scribes and artists held in high regard for their ability to create symbols that represented life, death, beliefs, and daily affairs. The concept that words and images can harmonize to communicate complex ideas is deeply embedded in human history.

A special way of writing is the Pre Inka khipu. Khipu is a mathematical notation system that uses colours and knots to encode statistics, name-lists, and probably even messages. Yet we haven’t found and decode any example of the latest. Technical this is possible.

Historical examples of the transition between painting and writing, the logical formalisation of the informal informative.

Chauvet Cave, Bronze Age Tablets, Native American Tally Marks,

not to mention the most known example, the Namer-Tablet.

| Chauvet Cave around 30.000 BC |

Collection of Bronze Age Brotlaibidoles around 2500-1400 BC |

Native American Tally Marks Shoshoni rock art around 1800 or earlier |

|

|

|

The development should be mentioned of the Alphabet from the Egyptian Hieroglyphs and their formalisation process from pictures, pictographs. Also the development from pictographs, practice of other old writing systems like Cuneiform, Old Chinese, Mayan pre 500BC-1697ad 2, Aztec, Pre Inka khipu,

Introduction to Research: Why Painting is Like Writing, and an Afterthought on Programming

The main topic here is an intriguing one, exploring the parallels between painting, writing, and programming through concepts of automatic writing aka “Free Lines” and, “Account and Counting”.

The practice of painting, much like writing, is often seen as a deeply creative act rooted in personal expression, storytelling, and structure. Yet, beneath the apparent differences between brushstrokes and words lies a shared essence: both painting and writing rely on systems, syntax, and repetition within which creators shape meaning. Just as writers construct sentences and organize narratives, painters work with layers of colour, form, and composition, guided by invisible “grammars” or principles that give shape to their ideas. This study explores the conceptual overlap between painting and writing, proposing that both are forms of composition where each individual part - be it a word, brushstroke, or line - contributes to an emergent whole that conveys meaning.

In an additional perspective, we consider how programming, often thought of as purely functional, intersects with these artistic practices. Like painting and writing, programming requires both structure and creativity, as coders organize logic through syntax to produce functionality, sometimes even unpredictably beautiful outcomes. Through the lenses of “accounting and counting” and automatic writing with “free lines,” this research draws parallels among these three practices, revealing the surprising ways in which programming shares with art and literature a reliance on incremental construction, emergent patterns, and a balance between order and spontaneity.

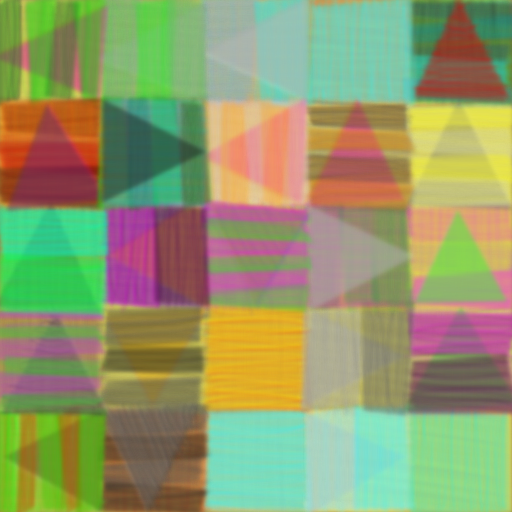

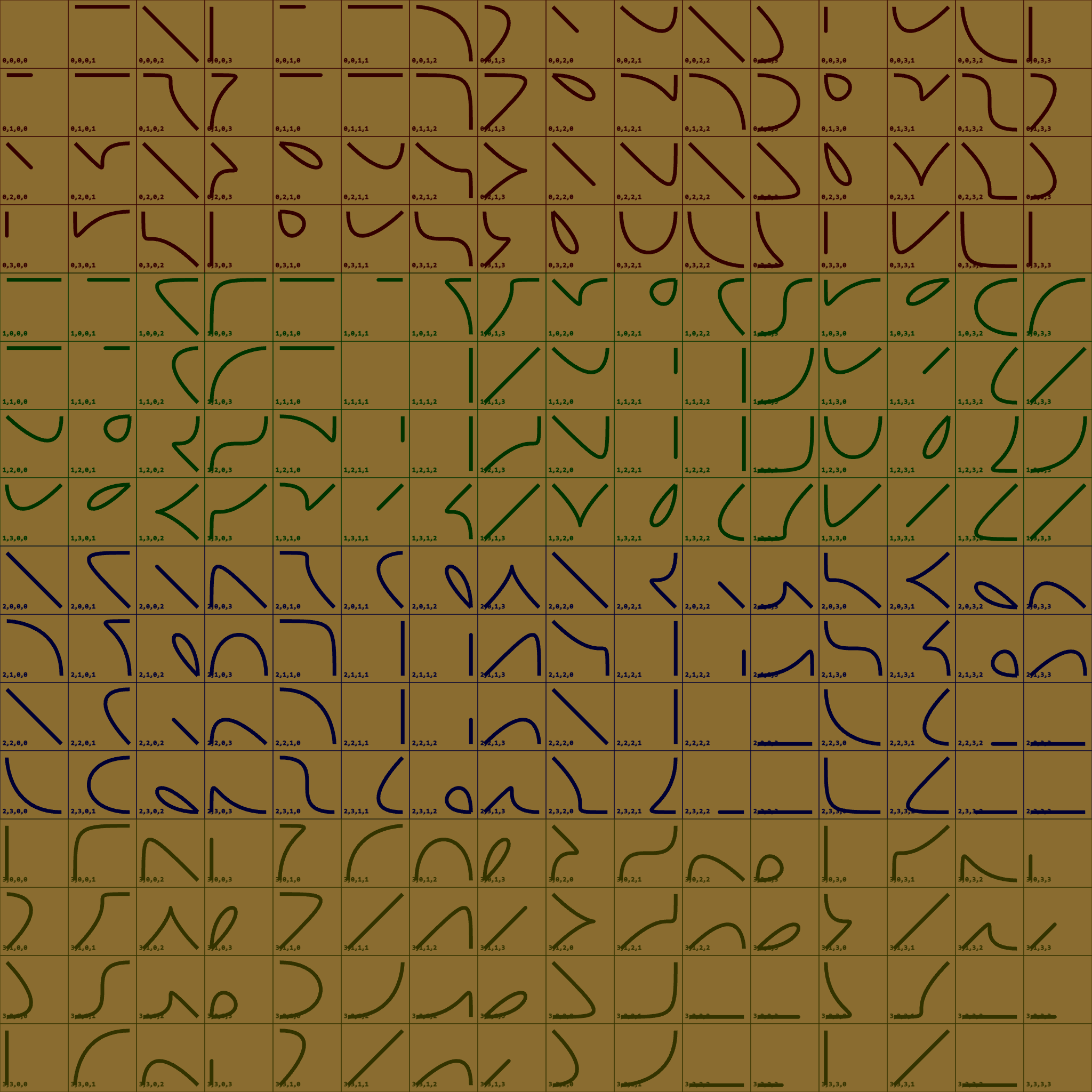

| lieschen mueller © Sep.2024 free lines 2 sections, several layers 4x4x1 image body, 6x6 grid |

|

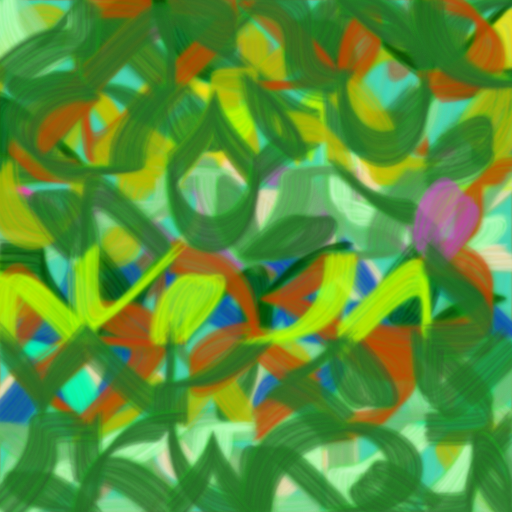

| lieschen mueller © Nov.2024 account and counting labyrinth, flat, 5x5 grid |

|

Now let’s break down the elements in these two exemplary images, which stand for the whole larger investigation, and consider how they might reflect these ideas.

technical commonalities

All images are based, developed in a 6x6 grid, to deployed either as flat print or an assembled 4x4x1 image body. There are variations of the grid and grid interpretation, enlarging the face of the image body or the height.

The “TweetRandom” library is used to generate the images. For testing purposes the source code was used as main random source. The images are self reflecting, self contained.

“Free Lines”

The first image, generated with a program on a 6x6 grid, presents an engaging opportunity to explore automatic writing with “free lines” as a method for understanding how painting is akin to writing and programming. Here’s an interpretation based on the concepts of automatic writing “free lines”:

1.0 The Motif “Free Lines”

As mentioned “automatic writing” is a common practice nowadays creating the “Free Lines” algorithm is a natural first choice. It actually emerged from a wave-line algorithm, which has been used in the “Virtual Gardens”-textures, later had been varied to create the Brice Marden generators, in honour of him.

1.1. Automatic Writing with “Free Lines” in the Image

- Automatic writing with “free lines” refers to the technique of letting the hand move freely, producing spontaneous, unplanned lines and shapes. In this image, the abstract, looping lines are layered and appear to have been created without a clear intention or outcome in mind.

- This unplanned approach reflects the core of automatic writing, where the writer or artist allows unconscious thoughts to guide the creation. In programming terms, this resembles a generative algorithm that introduces randomness or unpredictability to produce unique outputs.

1.2. Grid Structure as an Underlying Framework

- Although the image itself appears loose and spontaneous, it is based on a 6x6 grid, suggesting an invisible framework that subtly structures the output.

- This grid functions similarly to the underlying logic in writing or programming: in writing, it could be the basic rules of grammar or narrative structure; in programming, it might be a loop or function that constrains the output. The free lines play within this structured grid, much like how words or code must adhere to certain rules even as they convey unique meaning.

1.3. Embracing Randomness in a Controlled Setting

- The concept of “automatic” or “free” creation suggests an acceptance of randomness. Here, the colours and shapes, while abstract, follow the grid structure, allowing each section to host a different form or colour without disrupting the overall composition.

- This method is analogous to procedural generation in programming, where algorithms define constraints but allow variations within them. Similarly, in automatic writing, randomness is welcomed but ultimately shaped by the structure of language. This painting, like a program or written piece, balances unpredictability with underlying order.

1.4. Expression of Subconscious or Emergent Properties

- Automatic writing is often seen as a way to access the subconscious, allowing unfiltered ideas to emerge. In programming, this might relate to emergent properties - complex patterns or behaviours that arise from simpler rules.

- The image’s flowing, intertwined lines suggest organic growth or movement that seems unintentional yet cohesive. In the same way, code or words, when combined, can create meaning that feels greater than the sum of individual lines or statements. The image, though abstract, conveys a sense of movement and relationship among lines, as if capturing a subconscious “thought” or “idea”.

1.5. Free Lines as Syntax in Visual Form

- Each line in the image could be seen as a “free word” or “line of code” that contributes to an overall “syntax” or language of expression. The lines appear without rigid boundaries, yet together, they create a visual syntax that expresses a particular aesthetic or emotional effect.

- In writing, syntax and word choice communicate the author’s intent; in programming, each line of code is part of a sequence leading to a specific function. Here, the free lines serve a similar purpose, constructing an abstract visual language that viewers “read” as a cohesive image.

1.6. Painting, Writing, and Programming as Forms of Flow

- Both automatic writing and programming can invoke a *“flow state” - a sense of immersion where ideas and lines seem to generate themselves. This image, with its looping, interconnected lines, embodies that flow state visually.

- Just as a writer might free-associate words or a programmer might iterate through lines of code in a problem-solving state, the artist here lets the lines flow freely. The process of creating such an image, writing a story, or coding a program can all induce similar mental states, where structure and spontaneity balance to create a fluid, organic result.

1. Conclusion: Why Painting is Like Writing (or Programming) through Automatic Writing and Free Lines

- This image, created through a method of automatic, free-flowing lines within a grid, illustrates the balance between structure and spontaneity. The structured grid keeps the composition organized, but the free lines bring unpredictability and creativity.

- In writing and programming, we see the same dynamic: writers and coders start with a structure but allow for discovery and creativity within it. Free lines represent unplanned expression, while the grid symbolizes the invisible structure that guides creation, much like syntax in writing or loops in code.

- Ultimately, painting, writing, and programming can all serve as vessels for “automatic” expression - channels through which ideas, emotions, or functions emerge, often in surprising ways, from a blend of intention and improvisation.

From “Free Lines” To “Account And Counting”

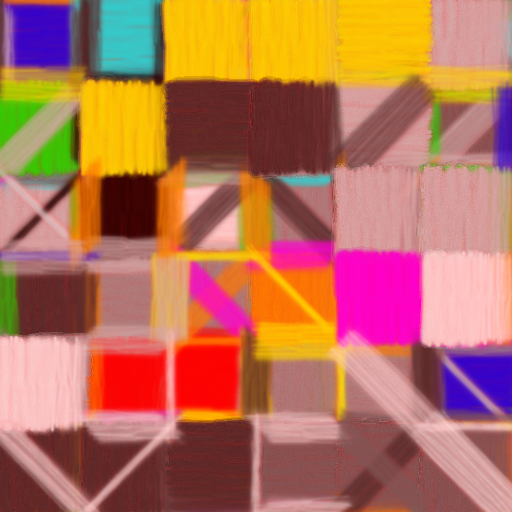

| lieschen mueller © Oct 2024 the full pseudo alphabet |

|

“Account And Counting”

A historical transitional form between painting and writing. Count, account, recount, counter, encounter (zählen, erzählen, nach[er]zählen, aufzählen in German) -> recording, reporting, storytelling via counting.

2.0. The Motif “Account and Counting”

The motif “account and counting” is the result of pre-historical observations, the prior experiments, the importance of time-based-systems in our culture, and the digital techniques in our daily life.

Within the “account and counting” the theme has been extend to reflect over the Western reading and writing traditions, not to say, it breaks them. Commonly known are LTR and RTL, which are two out of eight linear directions. Here these directions are used:

- linear, partially fragmented, 8 directions

- boustrophedon, a continuous flow, 8 variants

- circular, fragment with each new ring, inner to outer, outer to inner, clock- or counter-clock-wise.

- spiral, same amount of directions as circular, and a special case of circular

- meander, spiral and boustrophedon are subtypes of this. meander is multi directional

- labyrinth, a least one start point, but more end points are possible. It is very likely to be fragmented in figures

- fragmented, in single blocks/characters, groups/words, and full figures/lines

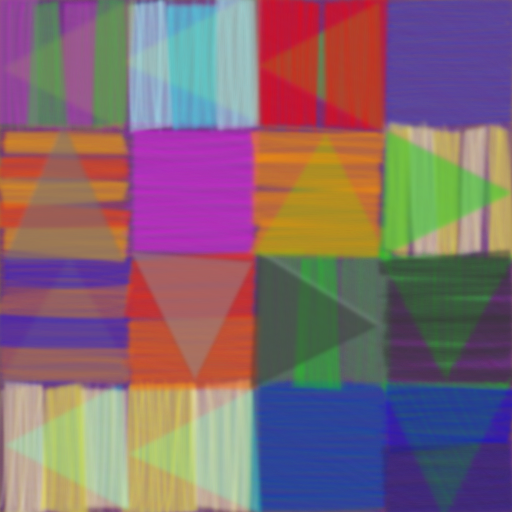

2.1. Structure and Repetition

- In the image, we see a grid structure composed of different coloured squares, each containing patterns - mostly triangles and lines - that seem to vary slightly within a set of constrained parameters.

- This structure resembles a “counting” approach in programming or writing, where each unit (a square in this case) is individually constructed but follows an overarching logic or system.

- In programming and writing, units (like lines of code or paragraphs) are sequential, building upon each other to form a cohesive whole. Here, each square contributes to the overall effect, suggesting that painting, like programming, relies on incremental development and a structured syntax.

2.2. Patterns and Syntax

- Each square in this grid functions almost like a “character” or “line of code” in a larger “program.” The repetition of shapes, like triangles and lines, suggests a visual syntax - akin to the syntax in language or code - that creates a coherent aesthetic language.

- This relates to the “account” in both writing and programming, where every word or line of code must fit into the logical flow, ensuring the narrative or functionality holds together. The painting here, though abstract, maintains internal rules governing colour, form, and structure, paralleling the way syntax rules guide written and coded compositions.

2.3. Algorithmic Thinking in Art

- The arrangement of geometric shapes within a structured grid suggests an algorithmic process - where rules are defined, and variations occur within those boundaries. The colours and shapes change, but only within a framework that gives the image coherence.

- Similarly, in programming, algorithms define boundaries within which specific outputs are generated. Painting can mimic this approach: artists establish rules (palette, form, layering) and then allow for creative variations within them. Thus, both painting and programming involve both strict parameters and creative freedom.

2.4. Accounting for Complexity

- “Accounting” here can refer to tracking or managing complexity. In writing, this could mean keeping track of narrative threads; in programming, it involves managing code modules. In painting, especially abstract art like this, accounting is about balancing colours, shapes, and patterns to achieve a harmonious composition.

- Each square here appears carefully calibrated in terms of colour and shape, suggesting a methodical approach to “accounting” for visual elements. The artist might be “counting” visual variables (such as how often green appears, how frequently triangles point in a particular direction), similar to how a writer or programmer would manage thematic or functional elements.

2.5. Painting as Visual Language

- Each square’s unique combination of colours and shapes forms a type of visual language, with each unit being a “word” or “code block” that communicates something within the image’s overall syntax.

- Just as writers string words together to produce a narrative and programmers arrange code to produce functionality, painters arrange colours, shapes, and lines to communicate visually. In this sense, painting becomes “writing,” where the artist is “coding” emotions, ideas, and aesthetics directly into visual form, which viewers “read”.

2.6. Infinite Variation within Finite Constraints

- The repeated but varied patterns suggest a logic of “infinite variation within finite constraints,” a common theme in writing, programming, and painting.

- Like programming, where loops or conditional statements create variability within constraints, each square here respects the grid but exhibits its unique colour and pattern. This is analogous to how different functions in code or sentences in writing adhere to an overarching structure but offer diverse outputs or meanings.

2. Conclusion: Why Painting is Like Writing (or Programming)

- This grid-style painting can be seen as a “program” where each square represents a “line of code” or “sentence,” contributing to a broader “narrative” or “functionality” of the artwork.

- The artist uses visual “accounting” (balancing shapes, colours, patterns) and “counting” (repetition and variation within each square), akin to a writer’s or programmer’s way of organizing thoughts, functions, or classes.

- In both painting and programming, there’s an underlying logic guiding creation, and once established, variations are explored within that logic, blurring the lines between structured creativity (programming/writing) and freeform expression (painting).

- So, in interpreting this image, we can see it as a “visual program” or “abstract story,” where each square functions as a “unit” of meaning, assembled according to a set of rules. The artist’s role mirrors that of the writer or programmer, setting constraints, making choices, and building complexity through iterative patterns - ultimately constructing an experience viewers can interpret, akin to reading or running a program.

Comparative Analysis of the Images and Final Conclusion

Let’s examine both uploaded images - the free-form, looping lines within a 6x6 unit grid, and the 5x5 grid-based composition with triangles and colours - to reach a cohesive understanding of why painting can be seen as similar to writing and, by extension, programming.

The first Image: Automatic and Free Line Expression within a Grid

- The first image, while still grid-based, diverges from rigid structures and embraces spontaneity with free-form, looping lines. This technique resembles “automatic writing,” where thoughts and associations are recorded freely, without strict intention or structure. Here, we see randomness and fluidity, yet the presence of a 6x6 grid provides subtle boundaries, just as syntax or structure frames freewriting or unconstrained code generation.

- This free-form approach evokes the flow state of creativity found in both writing and programming. In writing, automatic or stream-of-consciousness techniques allow ideas to surface without interference; similarly, some programming approaches embrace randomness or emergent properties to explore new possibilities. The image demonstrates how creativity can arise from seemingly chaotic, free-form elements, balanced within an implicit structure.

The second Image: Structured Patterning in a Grid

- The second image uses a 6x6 grid to organize a repetitive series of triangles and colour blocks. Each square serves as an individual unit with its own unique pattern, yet all follow an overarching set of rules. This structure echoes a foundational concept in writing: each sentence or paragraph functions as a part of a larger narrative, contributing to the theme or message. Similarly, in programming, each line of code serves a function within the program, structured within loops, conditions, or classes that create a coherent system.

- This image highlights “accounting and counting” as a method, illustrating how each square can be seen as a unit that both stands alone and fits within a larger pattern, much like words in a sentence or functions in code. The repetitiveness, combined with slight variations, emphasizes how systems can produce complexity through incremental changes - much like how narrative emerges from words or functionality emerges from code.

Final Conclusion: Painting, Writing, and Programming as Structured Expressions of Creativity

Both images illustrate the relationship between structure and spontaneity across painting, writing, and programming. The second image highlights the use of “accounting and counting,” showing how incremental, repeated units create complexity within a framework, akin to constructing a narrative or a program. The first image, with its automatic writing or “free lines,” shows how free-form creativity can emerge within subtle structural constraints, resonating with spontaneous writing and generative programming.

In conclusion, painting, writing, and programming each require both rules and creative deviation. Whether it’s a painter filling a canvas, a writer drafting prose, or a programmer designing code, all three rely on an underlying structure - be it a grid, syntax, or algorithm - to shape the final output. The unique balance between structure and freedom found in each discipline allows for an expression that feels both intentional and spontaneous, revealing that at their core, painting, writing, and programming are each about constructing meaningful, emergent systems. These systems guide creators as they transform simple elements into intricate, interconnected wholes, bridging the gap between logic and artistry.

Appendix

Examples of all image motifs for this artistic epidermic research:

| Free Lines on a 6x6 grid |  |

|

| Free Lines in sections and layers |  |

|

| Pseudo Letters |  |

|

| Only Straight Pseudo Letters with blocks |  |

|

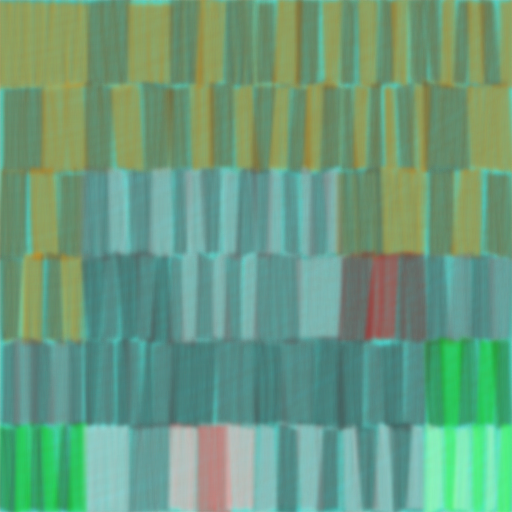

| Account and Counting Linear |  |

|

| Account and Counting Boustrophedon |  |

|

| boustrophedon image bodies |  |

|

| Account and Counting Circular |  |

|

| Account and Counting Spiral |  |

|

| Account and Counting Meander with triangles |  |

|

| Free Lines second variation |  |

|

| Account and Counting Meander with triangles, blocks, and pseudo letters |

|

|

| 3D Account and Counting: 4x4x1, 5x5x1, 6x6x1, 1x1x1, 2x2x2, 3x3x3 |

|

|

| Words on Account and Counting Meander |  |

|

| Word Lines 4x4x1, 2x2x2 |  |

|

| Account and Counting Labyrinth |  |

|

1

2

Tayasal, on Mayathan aka Itzá Noh Petén („City Island“), last Mayan state conquered 1697 by Spain, 1 year before the start of the industrial revolution (patent steam engine)