Painting Is Like Writing vice versa

This paper tries to explore the deep connection between painting and writing, focusing on how both mediums function as forms of accounting, recounting (narrating or reporting) and the principle of counting (measuring, reckoning, or organizing). Both painting and writing serve as powerful tools for communication, capable of evoking mental imagery - what coins the term “mind-pictures”. These mind-pictures transcend a medium itself, drawing the viewer or reader into a world of ideas, emotions, and symbolic representation.

By examining the parallels between these two art forms - such as their shared ability to translate abstract thoughts into visual or written form, the creation of vivid mental images, reliance on composition and structure, use of symbolism, and their storytelling power - the examination reveals how painting and writing are deeply interconnected. In the act of accounting, both the painter and the writer recount a narrative or convey an experience, guiding the audience through the representation of external and internal worlds. Just as a painting tells a story through its visual elements, writing communicates through words, each sentence forming brushstrokes on the canvas of the reader’s mind.

The statement

painting is like writing

“Painting is like writing” - and vice versa - is the saying.

A thought that pops up from time to time.

In this research the commonalities are addressed by programming a course

of image generators investigating this topic.

The research does not approve this saying, yet it is giving some reasoning

of why this is a somewhat valid thought, from the historical timelines

to nowadays art practices.

Thus, overall it demonstrates that “Painting is like writing”,

and writing is like painting, as both engage the observer’s imagination,

offering a dialogue between the artist’s intent and the audience’s

interpretation. Ultimately, both are forms of storytelling and emotional

expression, where acts blend to shape the mental and emotional landscapes they evoke.

Who said “painting is like writing” - some examples and variations of the saying.

- Picasso “painting is like writing (a diary)”,

- Amy Sillman “For me painting is like writing. I like doing it myself.”

- Voltaire “Writing is the painting of the voice”

- Horace, the ancient Roman poet, coined the phrase “ut pictura poesis” (as is painting, so is poetry) in his “Ars Poetica

- Leonardo da Vinci famously stated, “Painting is poetry that is seen rather than felt, and poetry is painting that is felt rather than seen”

- Wassily Kandinsky wrote extensively on the relationship between painting and other art forms. In his book “Concerning the Spiritual in Art,” he compared the visual elements of painting to musical notes and literary techniques

- and many others

1

Most artists focus on the poetic aspect of this common saying, others lay focus onto the daily practical. But all of them, writers, artists, philosophers, see the transition and the transfer between the arts. And sometimes not just between painting and writing, but between all the arts, acting, writing, painting, sculpture, music, dance and architecture.

This is where we must now consider programming not only as a functional tool and solution, but also as a new art form.

Why “painting is like writing” vice versa in one way or another:

… like programming -> programming as a transitional technique between writing and painting. Write a program in a mathematical language to generate, draw paintings.

Who practiced such statement in art

automatic writing, book/track-keeping, algorithms (wordplay: algo-rhythms)

the transition between painting and writing

maps, counting as storytelling - with marks, accountable order. old writing system utilizing pictograms aka formalized pictures, but this is already the moment behind the conceptual transfer from drawing to writing. Observation there: first writings are sketchy fragments, than lists, at last sentences, complete texts - writings that draw the full picture(s). Along side this development we see the division emerging between the image and the text. spreadsheets and playfields, boards like checkerboards, but also “American football” do share those patterns.

counter, encounter, account, recount, …

prelude

L-O-V-E, a circle poem played with/on/by a(two) “Reactive Canvas”(es).

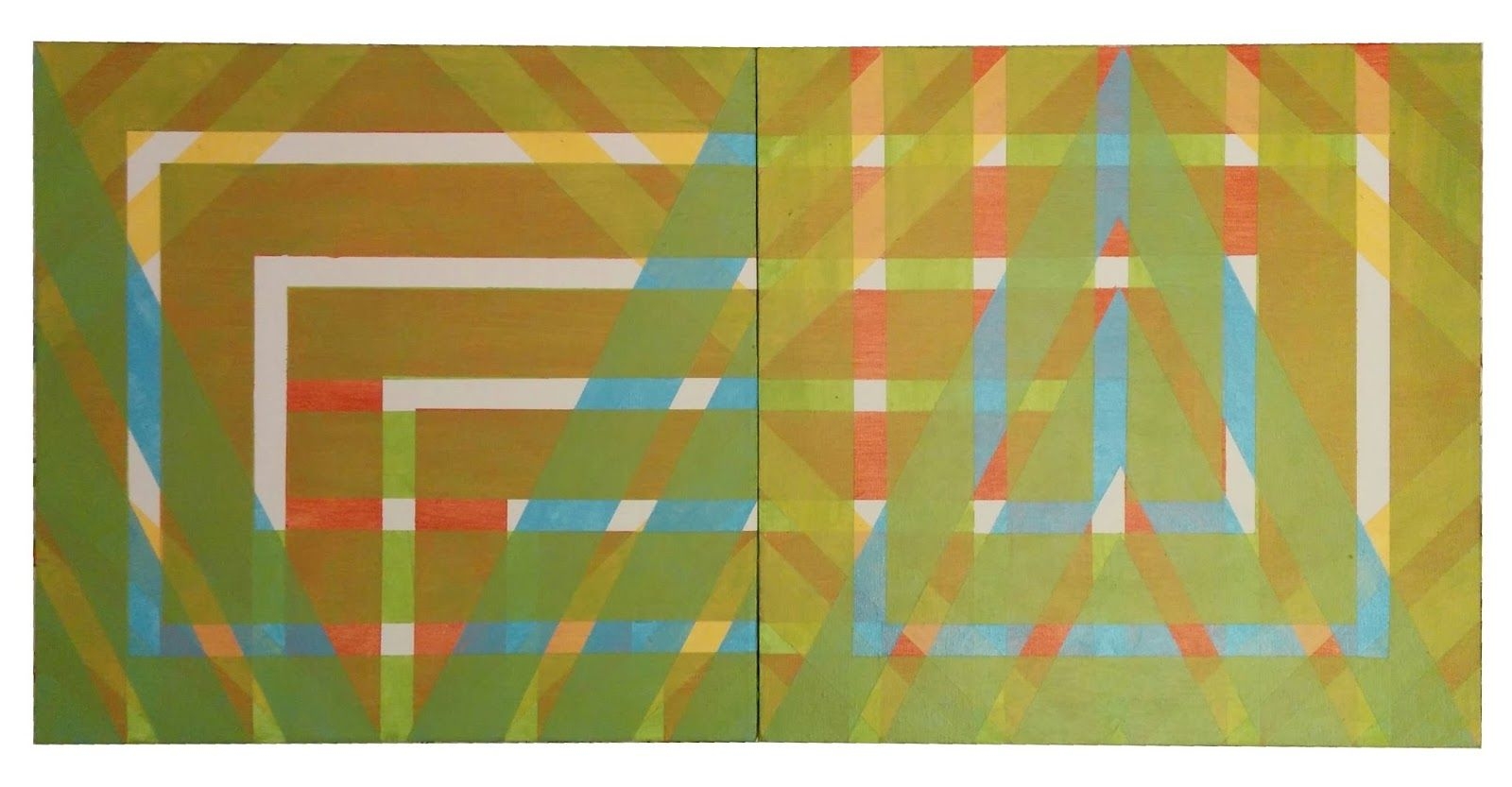

| lieschen mueller, break in the frame © 2014-15 |

|

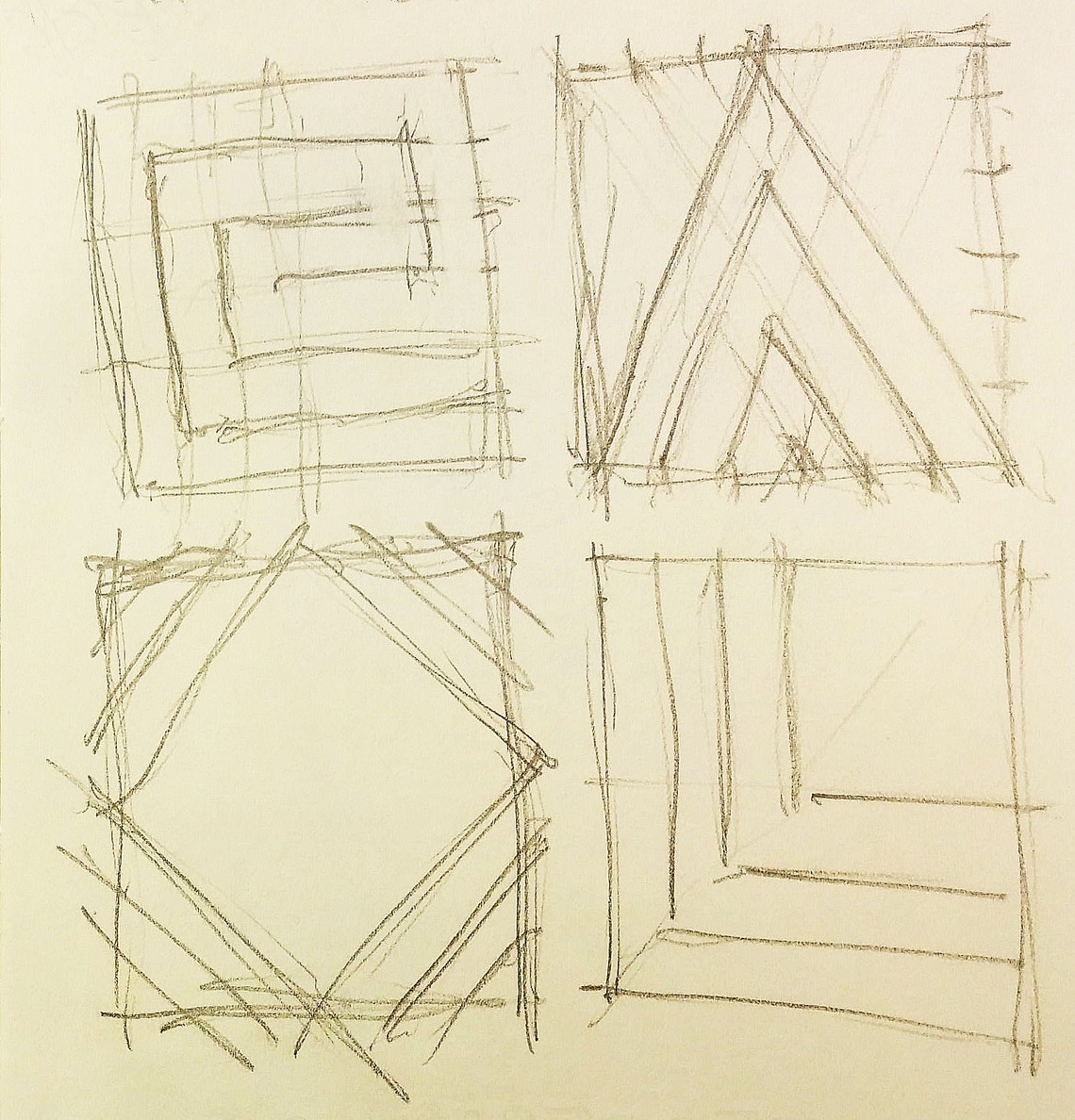

| sketch for break in the frame © 2014-15 |

|

first instalment

Testing the idea started with the concept of “Free Lines”. “Free Lines” follows the idea of automatic writing and free flow (body) movements. Automatic writing is well know principal in the 20th century arts. See the practice of Hilma Af Klint, Antoni Tapies, the surrealist movement in general, and Cy Twombly among many others. There are many variations of this idea, following conception is just another implementation.

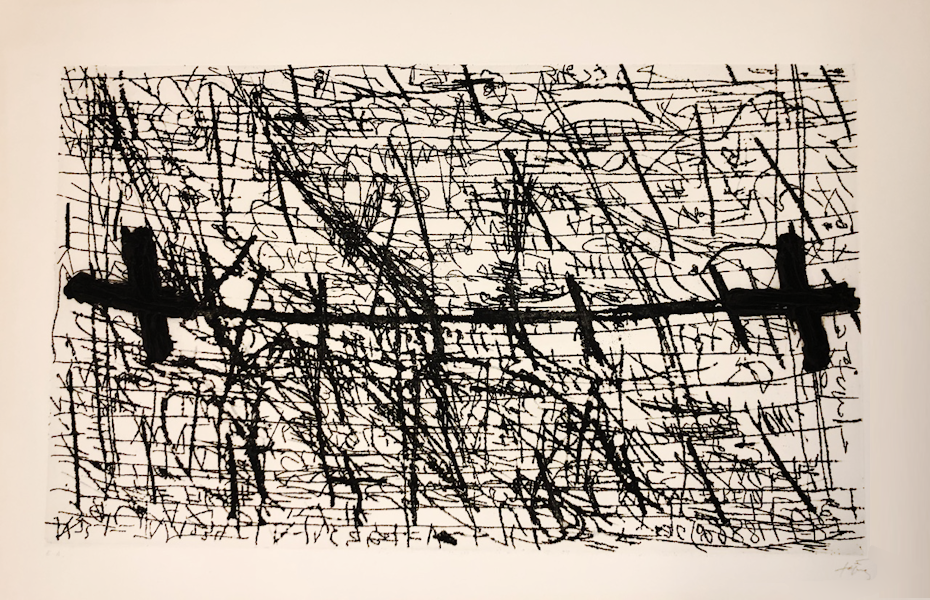

| Cy Twombly, Bacchus, 2008 |  |

| Antoni Tapies, Graphismes et deux croix, etching |  |

the first draft

On a 6x6 unit grid with half units, overall having 13 grid points in columns and rows, the program generates freely flowing curved lines connecting the grid points or using them as control-points.

The reason for a 6x6 grid is, this page/paper/canvas assembles into a body, which has a 4x4 units face with an elevated border frame of height 1 unit. The painting is al over the corpus. This is a prerequisite, which applies to all experimental instalments and beyond, as long it is not indicated otherwise.

The line colours may change pseudo randomly, as the program depends on text inputs to generate those numbers. The tweetRandom-library is used. Lines themself have a brush structure, the colour is a mix of foreground, ground and shadow colours in 2d implementations, furthermore in 3D a light source colour is applied.

In a subsidiary iteration the experiment divides the canvas into halves (, quarters, …) and levels. Per level the program fills only one half with “Free Lines”, leaving the other half blank. The pictures appear to have more structure, more organized composition over the free “calligraphic” look and feel of the full board.

observations and takeaways

- At the edges where the frames folds the image is broken. Parts of the information, the lines, are lost to build the structure.

- Something feels wrong, what will expose itself and clarify why later on.

- the smaller the grid becomes, the more the flow is hindered and looks more like a character.

- colour obfuscates the repetitions of patterns and applicates a more painterly

presence to the composition

some examples

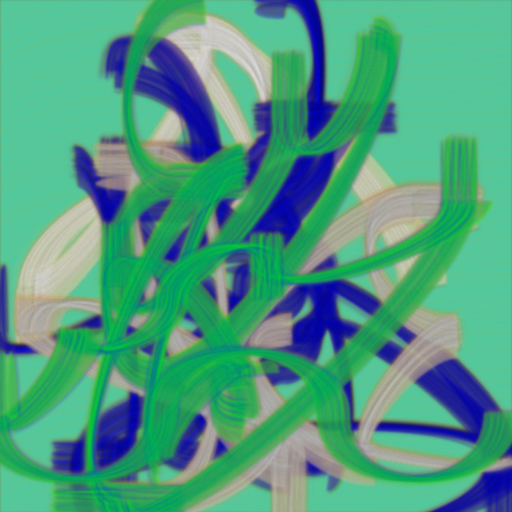

| lieschen mueller | © June 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| free lines on the grid collection_bm_wave_10.html |

automatic writing free lines on the grid |

free line automatic writing in a half block |

|

|

|

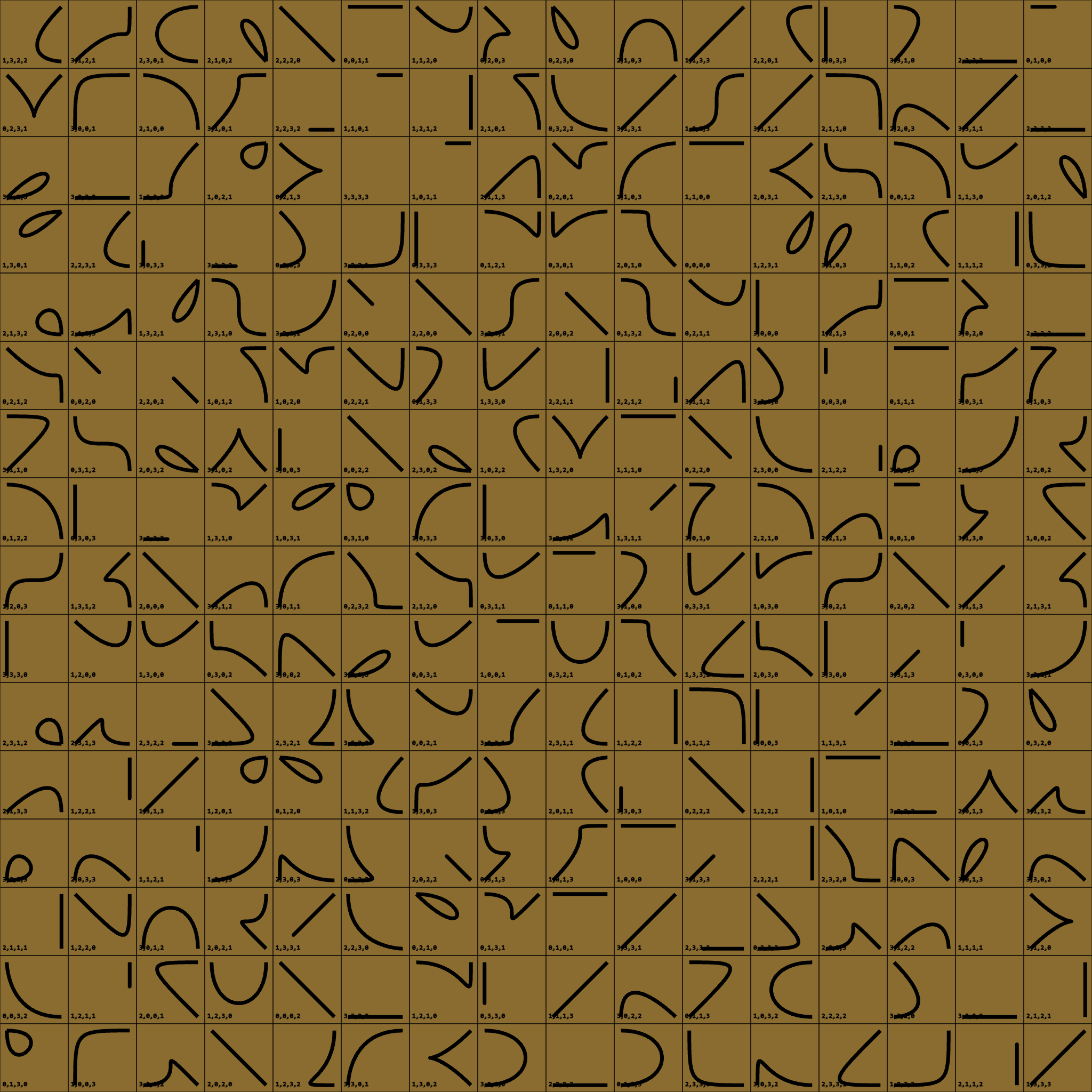

pseudo characters on a 1x1 grid

Because smaller grids show a more and more character like appearance, this fact led to next iteration of the programs.

implementation

On the 6x6 grid 36 single-grid-blocks are painted. A single-grid-block shape a pseudo character. A single-grid-block has 4 edge points. Those points are used as start-, control-, and end-points for a curved brushstroke line. The emphasis of the stroke can have different directions, orientations, and colour variations.

how many pseudo characters are possible?

| lieschen mueller |  |

reducing, focusing the characters on linear appearance and the block, only.

image results

| lieschen mueller | © July, Aug 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

the learnings

- Programming and therefore image generation is biased by the Western writing and reading traditions. It needs a lot of effort in programming to circumvent the effect and even more commitment to reduce the influence on ones thinking. It can hardly be annulled. That’s what felled wrong.

- Still the edges are compromised.

- Reducing the sum of character makes the picture more a pattern painting.

- Same for the filled 1x1 unit block brushstroke.

- The palimpsest affects condenses the writerly appearance down to a composition in left to right lines.

interludes

analysing the results so far

development of a new thought

a look back into the pre-historical past

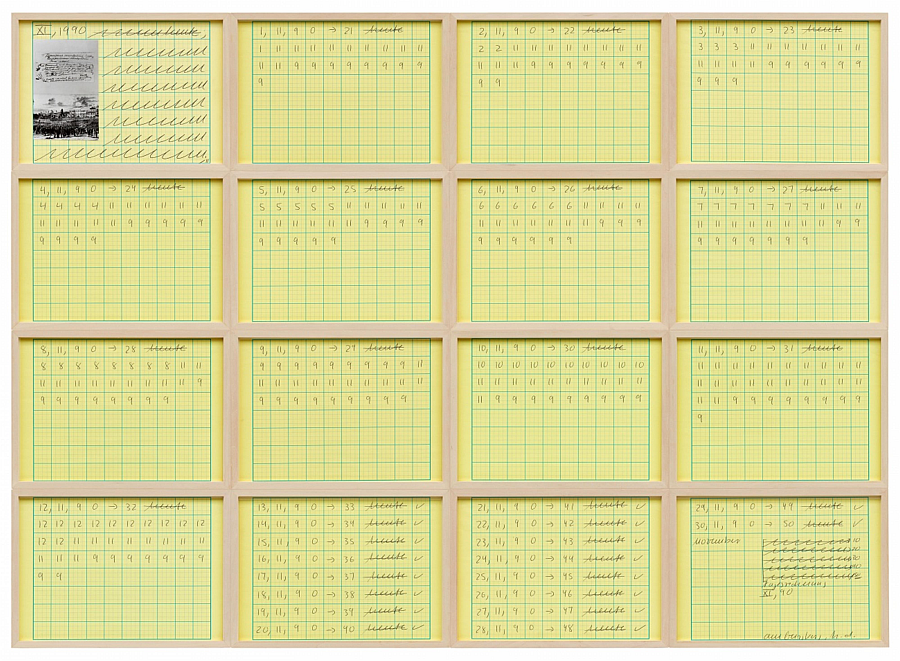

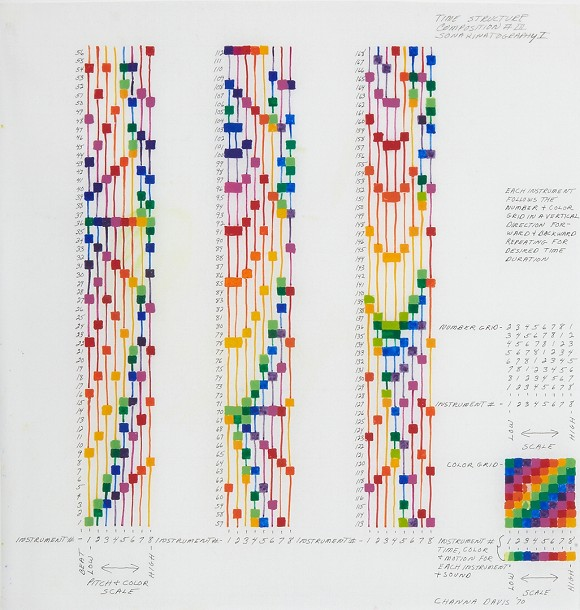

Chauvet, Lascaux, …, Hanne Darboven, Channa Horwitz, (On Kawara, Yayoi Kusama, Jenny Holzer, etc.)

| Chauvet Cave |  |

| Chauvet Cave, Red Dots Cluster |  |

| Niaux Cave in France |  |

| Hanne Darboven, §Dostojewski, 12 Monate (November)”,1990 hanne-darboven.org |

|

| Channa Horwitz, Time Structure Composition #III, Sonakinatography I, 1970 https://www.lissongallery.com/artists/channa-horwitz |

|

Counting Systems

Counting systems have been an essential part of human development, shaping how we understand and interact with the world. From early tally marks scratched into cave walls to the complex numerical systems of advanced civilizations, these methods of counting reflect both practical needs and abstract thinking. In this chapter, we will explore the evolution of counting systems, comparing the advantages of dozen-based and decimal systems, examining the influence of natural patterns like Fibonacci and prime numbers, and revisiting ancient forms of counting such as finger counting and tally marks. These diverse approaches reveal the richness and variety in how humans have sought to quantify and make sense of their environment over millennia.

Dozen vs Decimal

Throughout history, different counting systems have emerged based on practicality and cultural preferences. The dozen-based system, which operates in multiples of 12, has long been preferred for its versatility. It divides easily into halves, thirds, and quarters, making it particularly useful in trade, measurements, and calendar systems.

The decimal, or base-10 system, is more prevalent today, largely because of its alignment with human anatomy—ten fingers on which we naturally count. Though the decimal system is mathematically simpler, especially in modern computation, the dozen system’s divisibility makes it ideal in certain applications, especially in trade, construction, and timekeeping.

Other Counting Systems

Beyond the dozen and decimal systems, many other counting systems have evolved. The sexagesimal (base-60) system, used by the ancient Babylonians, still influences how we measure time (60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour). Some cultures favoured base-20 (vigesimal) systems, often linked to counting on both fingers and toes.

These systems reveal the diversity of human cognition and adaptation, reflecting the environment and needs of different societies. Even though many have fallen out of general use, they persist in various fields of mathematics, engineering, and historical scholarship. Binary, Octal counting, bits and bytes in the digital world.

other concepts than base-12 and base-10, numeric and non-numeric ones

Many other numeric and non-numeric systems of organizing and understanding the world exists that go beyond the familiar base-10 and base-12 systems. These systems have been used throughout history and in different cultures, often reflecting unique worldviews, practical needs, and symbolic understandings. Below are some examples of both numeric and non-numeric concepts used for counting, organizing, and interpreting the world.

Numeric Systems Beyond Base-10 and Base-12

1. Base-60 (Sexagesimal System)

- Origin: Used by the ancient Babylonians, this system divides numbers by 60, rather than 10 or 12. It was widely used in astronomy, geometry, and early mathematics.

- Applications:

- We still use base-60 in timekeeping (60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour).

- Degrees in a circle are measured in 360°, a multiple of 60, which comes from this tradition.

- Symbolic Meaning: Base-60 combines the practicality of both 12 and 10, as 60 is divisible by many numbers (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 15, 20, 30).

2. Base-2 (Binary System)

- Origin: Binary (base-2) is a mathematical system using only two digits: 0 and 1. It’s the foundational system for modern computing and digital technology.

- Applications:

- Binary systems represent data in computers (bits and bytes).

- Logic gates and modern algorithms rely heavily on binary thinking, where everything is reduced to choices or oppositions (yes/no, true/false).

- Symbolic Meaning: Binary reflects the concept of duality, a key principle in many philosophical systems (light/dark, good/evil, order/chaos).

3. Base-5 (Quinary System)

- Origin: Base-5 systems, using five as the foundation, have been used by various indigenous cultures. This system is thought to derive from counting on one hand.

- Applications:

- Found in ancient Mayan numbering systems and other early cultures for practical counting.

- Some financial or commodity systems (such as tally marks) are built around groups of five.

- Symbolic Meaning: This system connects to basic human anatomy (five fingers), making it deeply human-centred and practical for small-scale transactions.

4. Base-20 (Vigesimal System)

- Origin: Used by the Mayan civilization and certain Celtic languages, base-20 systems count in units of 20.

- Applications:

- The Maya used base-20 for calendars, astronomy, and architecture.

- French language still retains traces of this system (e.g., the word for 80 is “quatre-vingts,” meaning “four twenties”).

- Symbolic Meaning: This system likely evolved from counting on both hands and feet (10 fingers, 10 toes), symbolizing completeness in a different way than base-10.

5. Base-8 (Octal System)

- Origin: Octal (base-8) is used in some computing systems, especially in earlier technologies and in fields like electronics and networking.

- Applications:

- Often used in digital circuits where 8-bit systems are common.

- Cultural significance: Certain cultures, such as the Yuki of California, used an octal system based on counting the spaces between fingers rather than the fingers themselves.

- Symbolic Meaning: In cultures that used octal systems, it reflected unique counting methods tied to their worldview and environment.

Non-Numeric Concepts of Organization

Beyond numeric bases, there are non-numeric systems of organization and understanding that provide alternate ways of framing reality, particularly in storytelling, time, philosophy, and culture.

1. Four Elements (Classical Elements)

- Origin: Many ancient cultures, including Greek, Chinese, and Indian traditions, categorized the world into four fundamental elements - earth, water, air, and fire.

- Applications:

- Used in alchemy, medicine, and early science to explain natural phenomena.

- In storytelling, many myths and cosmologies incorporate the four elements as archetypal forces that shape the universe.

- Symbolic Meaning: The four elements represent the balance of opposites and natural forces, a way to conceptualize the world through qualitative attributes rather than numerical measures.

2. The Five Phases (Wu Xing)

- Origin: In Chinese philosophy, the Wu Xing represents five phases or elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water.

- Applications:

- This system is used in Chinese medicine, feng shui, martial arts, and philosophy to understand natural cycles and relationships.

- It describes cyclical processes of creation and destruction, rather than fixed categories.

- Symbolic Meaning: The five phases reflect the dynamic and interconnected nature of life, where elements move and interact with each other in cycles, emphasizing balance and harmony rather than linear progression.

3. The Hero’s Journey (Monomyth)

- Origin: Joseph Campbell’s analysis of myth led to the concept of the Hero’s Journey, a non-numeric system describing a universal narrative pattern found in myths across cultures.

- Applications:

- Widely used in storytelling, particularly in literature and film, where the structure follows stages like the Call to Adventure, Crossing the Threshold, and Return.

- The journey itself reflects spiritual and personal growth, not bound to numbers but to symbolic phases of transformation.

- Symbolic Meaning: It portrays the cyclical nature of human experience, where the journey out and return is symbolic of growth, challenge, and renewal, much like the Meander metaphor discussed earlier.

4. I Ching (Yijing) Hexagrams

- Origin: The I Ching, or Book of Changes, is an ancient Chinese text that uses 64 hexagrams (combinations of six broken or unbroken lines) to represent different states and transitions.

- Applications:

- Used for divination, philosophical contemplation, and understanding dynamic change.

- Each hexagram represents a specific combination of yin and yang, emphasizing balance and continuous flow.

- Symbolic Meaning: The I Ching is a way to interpret the interconnectedness of all things. It reflects the idea that reality is in constant flux, rather than being governed by rigid numeric systems.

5. The Seven Chakras

- Origin: In Hinduism and various esoteric traditions, the chakra system represents seven centres of spiritual energy in the body.

- Applications:

- Used in yoga, meditation, and spiritual practices to understand physical and spiritual well-being.

- Each chakra represents a different aspect of life or consciousness (e.g., survival, love, wisdom).

- Symbolic Meaning: The chakras embody a non-numeric way of categorizing human experience, one that’s holistic and interconnected, reflecting different layers of existence from the material to the spiritual.

Natural Counting Systems: Fibonacci and Prime Numbers

Nature itself offers its own methods of counting. The Fibonacci sequence, a series in which each number is the sum of the two preceding ones, appears frequently in natural growth patterns—from the arrangement of leaves on a stem to the spiral of seashells. Similarly, prime numbers, indivisible except by 1 and themselves, hold a foundational place in mathematics and nature. These natural counting systems illustrate the deeper mathematical patterns underlying the world around us, showing how both abstract and practical counting can intersect.

There are systems based on Fibonacci and prime numbers used in both mathematical and artistic contexts, and they can be related to the concept of accounting, recounting, and mind-pictures. While these systems are more frequently found in mathematics, nature, and design, they can be creatively applied to storytelling, writing, and visual art.

Let’s break this down by considering how painting is like writing and how mind-pictures are evoked using these number systems.

Fibonacci-Based Systems in Art and Writing

The Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …) is closely related to the golden ratio, which has been used for centuries in composition, architecture, and design. Artists and writers use Fibonacci-based structures to create aesthetic balance, rhythm, and harmony in their works, which directly ties into how these mediums are constructed and perceived.

In Painting:

The Fibonacci sequence is often used to design the composition of paintings. Many classical works, from Leonardo da Vinci’s to Salvador Dalí’s, use the golden ratio to position key elements, ensuring a naturally appealing and balanced layout.

Example: Dalí’s “The Sacrament of the Last Supper” is often cited as being structured according to the golden ratio, with proportions and spacing evoking a harmonious image that draws the eye to specific focal points, creating an organized “account” of the scene.

In Writing:

In literature and storytelling, Fibonacci-like structuring can create a narrative rhythm that mirrors natural patterns of growth and progression, offering a layered and expansive story that slowly builds, much like the expanding Fibonacci sequence.

In a novel or poem, chapters or verses can be structured around Fibonacci numbers, starting small and growing in length or complexity. This mirrors the way ideas or tension can “unfold” like in a Fibonacci spiral.

For example, a short story could start with a single event (1), followed by two parallel actions (2), three interwoven themes (3), and continue building with five interconnected characters (5), creating a narrative spiral that deepens as the story progresses.

Prime-Based Systems in Art and Writing

Prime numbers (2, 3, 5, 7, 11, …) have unique mathematical properties because they are divisible only by 1 and themselves. These numbers create a sense of irregularity, structure, and mystery, often applied in artistic and literary forms to evoke complexity and patterns hidden beneath the surface.

In Painting:

Artists might use primes to define spacing, proportions, or repetitions in a composition. Using prime numbers in this way creates non-repeating, organic patterns, which can lend an artwork a sense of unpredictability or uniqueness.

Piet Mondrian’s grid paintings and Islamic art’s geometric designs both use systems inspired by primes to create patterns that seem orderly yet non-repetitive, drawing the viewer into deeper contemplation, just like the flow of a narrative account.

In Writing:

Prime numbers can structure poems, chapters, or acts in a play. Prime-based systems might create unexpected twists, where crucial events or revelations happen at the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 11th points in the narrative, guiding readers to count forward in anticipation while also keeping them off-balance due to the non-linear progression. Experimental poetry or modernist prose, such as James Joyce’s Ulysses, could incorporate prime numbers in paragraph lengths, sentence structures, or chapter divisions, creating a complex, unpredictable rhythm that challenges readers to “decode” the narrative structure. Relevance to Mind-Pictures and Accounting The application of Fibonacci or prime systems to both painting and writing creates structured forms that appeal to the mind’s sense of order and aesthetic harmony. These structures help build and reinforce mental images in unique ways:

Mind-Pictures in Painting:

Fibonacci and prime structures direct the eye naturally, allowing the viewer to mentally “account” for the flow and composition of the artwork. The viewer unconsciously organizes the visual information, counting and recounting the elements in the painting, which builds the mental narrative of the piece.

Mind-Pictures in Writing:

When Fibonacci or prime systems are used in writing, they subtly shape how readers mentally structure and account for the unfolding story. Readers, while unaware of the mathematical pattern, still respond to the ebb and flow, creating vivid mental imagery that aligns with these structural cues.

For instance, a Fibonacci-structured plot may build momentum, drawing the reader deeper into the story as each new layer is added. Conversely, a prime-structured story may introduce surprises and asymmetry, engaging the reader’s imagination to reconstruct events or ideas in novel ways.

Painting is Like Writing – Using Fibonacci and Primes

Both Fibonacci and prime-based structures are, in essence, accounting systems for how a story or image is constructed and experienced. They help organize complex visual and narrative elements, much like how an accountant organizes numbers to build a financial report.

Accounting in Painting:

Artists use these number-based systems to structure their visual storytelling. The act of “accounting” in this sense is the careful counting of proportions, patterns, and relationships between elements in the artwork to create a harmonious or dynamic composition. Accounting in Writing:

Writers can also “account” for narrative flow using these systems, creating a scaffold on which the counting of words, sentences, or chapters happens according to Fibonacci or prime patterns. This hidden structure adds depth and rhythm, subtly guiding how the reader forms mind-pictures and interprets the unfolding narrative.

powerful tools for organizing

While not traditionally thought of as accounting systems, Fibonacci and prime numbers serve as powerful tools for organizing and counting elements in both visual art and writing. They allow creators to structure complex, organic forms that naturally engage the viewer or reader’s imagination, helping to construct vivid mental images—or mind-pictures—that tell a deeper story. By intertwining these number systems with narrative and visual elements, both painting and writing become forms of accounting, recounting, and creating deeply immersive experiences.

Tally Marks and Finger Counting

Primitive counting systems often relied on the body or simple marks. Tally marks, for instance, are an early and intuitive method of counting, with each mark representing one unit. Finger counting is another natural method that predates written numerals, where each finger represents a number, often grouped in sets of ten. These forms of counting are direct, physical, and tactile, offering a bridge between the concrete and abstract. They represent the earliest stages of numerical understanding, where numbers were visual and embodied rather than purely symbolic.

The Draft

why is counting is transitional between painting and writing

“Account And Counting”

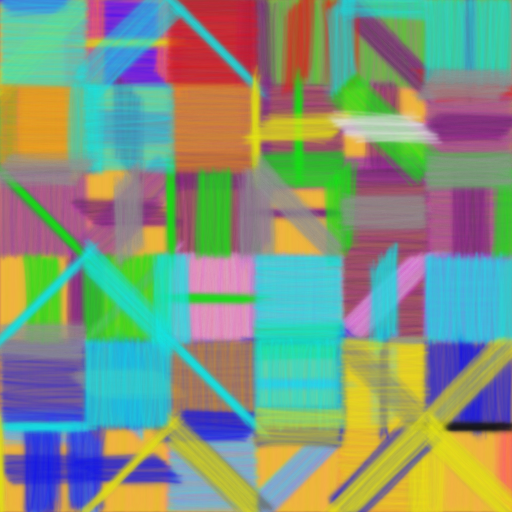

counting from 0, 1 to 5 on a variation of grids (4x4, 6x6, 5x5, …)

“Account And Counting” instalments for now

border frame is always a circular line, face is a 4x4 grid, 6x6 grid, linear, boustrophedon, circular, spiral

example pictures

| lieschen mueller | auto write nxn | © Aug 2024 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

triangle variation

| lieschen mueller | auto write triangle variation | © Aug 2024 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

finding the ideal literature source(s)

Marlow’s

- Doctor Faustus Goethe’s

- Faust Fragmente (Faust fragments)

- Urfaust

- Faust Teil 1 (part one)

- Faust Teil 2 (part two)

- Farbenlehre (psychology and physics of colours)

- Metamorphosis (biological thought poetics about flowers)

- Versuch die Metamorphose der Pflanzen zu erklären (essay)

- die Metamorphose der Pflanzen (poem)

account and counting Faust

Homer’s

- Iliad (troy)

- Odyssey James Joyce’s

- Ulysses

account and counting Odyssey

meander

The concept of Meander - a winding, non-linear flow - can serve as a powerful metaphor for understanding the relationship between time, flow, and storytelling, especially when viewed through the symbolic lens of base-12 (higher order) vs. base-10 (human order).

Meander as a Metaphor for Time

The Meander pattern, named after the winding Meander River in ancient Greece, represents a path that is non-linear, fluid, and cyclical. This is significant in storytelling and timekeeping because it contrasts with the linear, rigid structure of time often seen in base-10 or modern systems.

Cyclical Nature of Time (Base-12): In ancient cultures, time was often viewed as cyclical, much like the flow of the Meander River. Base-12 systems - used for dividing the day into 12 hours or the year into 12 months - reflect this cyclical understanding of time. This view is more fluid, allowing for a sense of eternal return, where time is not strictly linear but loops and flows like a river, often seen in myths and cosmic cycles.

Linear Time (Base-10): Modern systems of timekeeping, influenced by base-10, emphasize progression and precision. The decimal system promotes a linear, measured understanding of time, focusing on human experience and practicality. Time becomes a sequence of units - hours, minutes, seconds - designed for efficiency, not the fluid, cosmic flow seen in earlier symbolic systems.

Meander and Storytelling: Non-Linear Narratives

In storytelling, the Meander pattern can represent a non-linear narrative, where the flow of events isn’t strictly bound by a rigid structure but meanders through time, space, and meaning, much like ancient myths or epics. This mirrors the base-12 concept of higher order storytelling, where stories align with the rhythms of the cosmos, cyclical time, or divine order.

Non-Linear (Meander) Storytelling: Stories that unfold in a meandering fashion like epics or myths - often mimic the flow of the Meander. They may not follow a strict sequence of cause and effect but instead weave through various arcs, side stories, and recurring motifs. Examples include Homer’s Odyssey, where the hero’s journey is full of detours, reflecting the winding nature of fate and divine intervention. This type of storytelling connects to a base-12 philosophy, where narratives are cyclical, reflecting cosmic or divine order rather than human linearity.

In contrast Linear Storytelling (Base-10) “modern” storytelling, often influenced by base-10 logic, tends to be linear and goal-oriented. Stories are structured with a clear beginning, middle, and end, progressing toward resolution in a straight line. This approach reflects the practical, human-centred base-10 worldview, where time is linear, and narratives move forward in a measurable, predictable fashion. With the influence of other non-western traditions this changes again.

Flow and the Meander in Time and Accounts

The flow of time and resources in both storytelling and accounting systems can be understood through the Meander metaphor.

Repetitive Flow in Base-12 (Meandering Order) - the clock goes always in the round. Just as the Meander flows naturally and unpredictably, base-12 systems allow for more natural, fluid partitioning in counting and time. In ancient accounting, the base-12 system allowed for easy division into parts (1/2, 1/3, 1/4), making it flexible and adaptable to changing circumstances, much like the winding flow of a river. This flexibility is akin to how a meandering story can adapt and evolve, touching on different themes, characters, and events without a rigid structure.

Flow in Base-10 (Linear Precision) systems, which focus on efficiency and standardization, reflect a more linear, precise flow of time and accounting. Here, time is measured in predictable, equal segments, and resources are divided into neat decimal fractions, emphasizing control, predictability, and human-centred logic. This is ideal for modern financial systems and linear storytelling, where clarity and progression are paramount.

Relevance to Storytelling and Human Experience

The Meander’s symbolic winding path offers insight into the way humans experience time, memory, and narrative:

The Non-linear human experience: Human memory and experience often don’t follow a straight line. Much like the Meander, memories resurface, repeat, and intertwine, creating a narrative flow that is cyclical and complex. Storytelling that embraces this meandering structure often feels more reflective of real life, where events are interconnected in ways that a strictly linear structure can’t capture.

Ancient Myth and Cosmic Storytelling, cosmologies, which often followed base-12 systems, reflect the meandering flow of cosmic time. These stories are deeply intertwined with the movement of celestial bodies and natural cycles, mirroring how time itself seems to loop and repeat in cycles. This is echoed in the winding structure of the Meander, where paths often seem to return to earlier points, much like recurring themes in mythic storytelling.

Broader Implications: Meander as a Bridge Between Systems

The Meander can be seen as a bridge between base-12 (cyclical, divine order) and base-10 (linear, human order). In storytelling, accounting, and timekeeping, it represents a synthesis of both worlds.

Meander as Higher and Human Order

Just as the river’s winding flow combines unpredictability with an underlying sense of direction, human narratives and systems blend the fluidity of divine order (base-12) with the practical needs of human life (base-10).

Some Hybrid Systems of storytelling, accounting, and timekeeping today reflect both principles. For example, while modern accounting is mostly base-10, the flow of time is still organized around base-12 systems (e.g., 12 months, 12-hour clocks). Similarly, while most modern narratives are linear, many also incorporate non-linear, meandering elements, as seen in movies with flashbacks, looping timelines, or multiple perspectives.

Meander a profound metaphor

The concept of the Meander offers a profound metaphor for how time, flow, and storytelling operate across different symbolic systems. In base-12, time and storytelling reflect a higher, divine order, cyclical and cosmic, much like the winding flow of the river. Base-10 represents human-centred logic, linear progression, and predictability. The Meander allows for the coexistence of both: fluidity within structure, where divine and human systems of time, accounting, and narrative flow together.

meander figuration

boustrophedon and spiral are highly specific subsets of the meander figuration - linear and circular are not because those brake the constant flow.

meander figure pictures

| lieschen mueller | © Sep 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

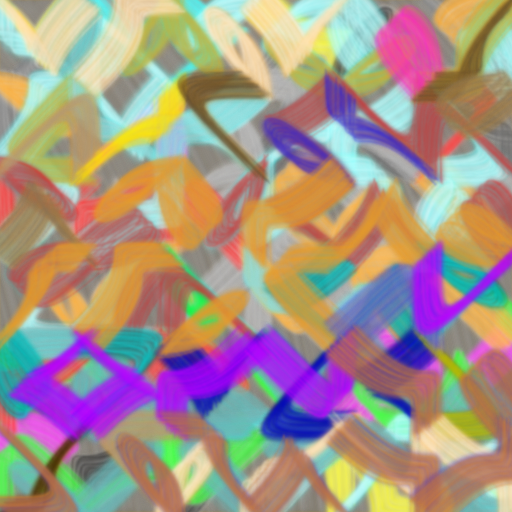

three dimensional enhancements

Three dimensional dilatation of the “accounting and counting” writing painting in linear, boustrophedon, circular, spiral and meandric traces gives what: account and counting Part4

more image examples

| lieschen mueller | © Aug, Sep 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

not so final conclusions

- programming a painting through writing in a numeric driven environment

- literature as a source of random noise

- significant “new”, because very old, spiritual, not selfish or traditional thinking

resume …

[resume, synopsis here]

| lieschen mueller | © June - Sep 2024 | |

|---|---|---|